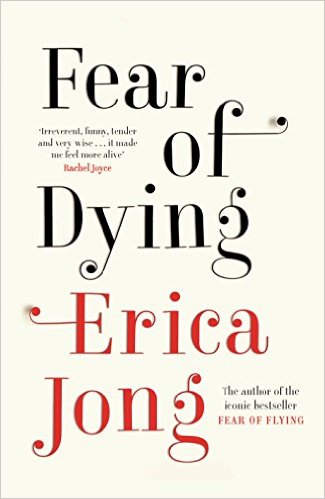

I was introduced to Fear of Dying by a friend after I’d read and reviewed Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying. Inevitably, there’s a temptation to compare, which I’ll attempt to resist. I’m of the same generation as the author, though a few years younger, so I’ve lived through the years she’s experienced and understand many of the events and ideas she refers to on a personal level.

The first novel, the one that shot her to fame at an early age, was revolutionary and daring in its treatment of sex at the time. This novel looks at death and, whilst it can be described as candid in its treatment of this often taboo subject, it certainly isn’t revolutionary.

We all reach an age when friends and parents die around us, vividly bringing home our own mortality. We reach a stage in life where death is closer than birth and where funerals are more common in our circles than births and weddings. It forces us to contemplate our own demise.

The novel is about ways of deflecting this influence, ways of avoiding the issue, ways of trying to deny it. Often this is partially achieved by simply living more in the moment, living each day as though it’s the last, living with gusto. Once again, the protagonist here engages with sex as a means of escaping aspects of her reality. I think there’s a metaphor here for the role of procreation in sex, even though, perhaps in fact because, such procreation is no longer possible for the woman at this age. Though, of course, the male has the ‘advantage’ that it remains a possibility right up to the time of death.

There is an unavoidable sadness in the decline of the woman into age, the descent into barrenness and the loss of that ability, which is deeply driven by biology, to carry new life. Perhaps that explains the enthusiasm older women have for their grandchildren. All these issues are touched on and some are examined in depth in the novel.

There are, for this agnostic British male, too many references to American Jewishness and its culture and tradition. Some of these references I found meaningless, in fact. However, the bulk of the book promotes links between all of us who have reached that ‘certain age’. It is easy to empathise with the characters, in spite of their excess wealth and material comforts: a state foreign to the vast majority of pensioners. It is the near obsession with endings that resonates with all of us.

I enjoyed the book, enjoyed the comedy and the tragedy, enjoyed the generational asides, enjoyed the satire and the sheer humanity of the work. It is a book I’m pleased to have read.